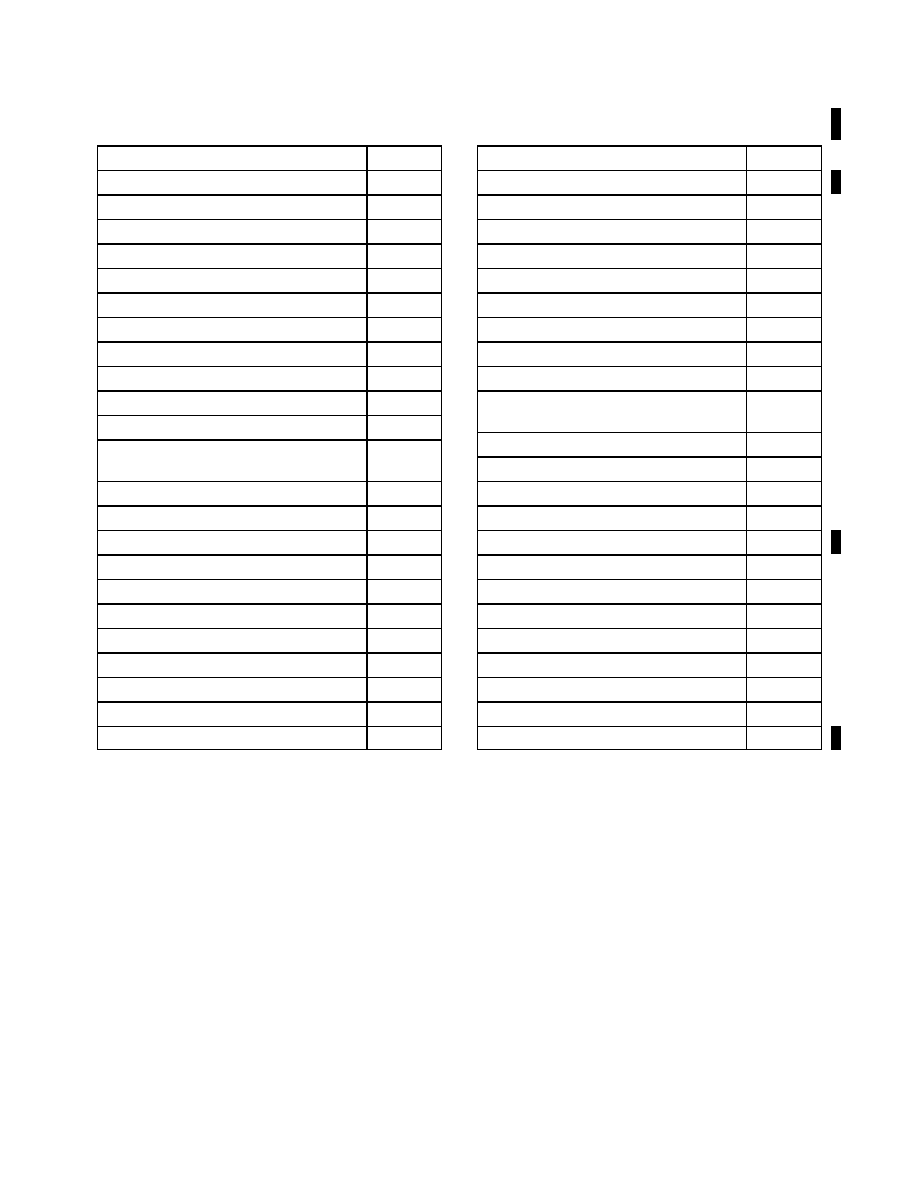

4/20/23

AIM

TBL 7

−

1

−

12

TWIP

−

Equipped Airports

Airport

Identifier

Andrews AFB, MD

KADW

Hartsfield

−

Jackson Atlanta Intl Airport

KATL

Nashville Intl Airport

KBNA

Logan Intl Airport

KBOS

Baltimore/Washington Intl Airport

KBWI

Hopkins Intl Airport

KCLE

Charlotte/Douglas Intl Airport

KCLT

Port Columbus Intl Airport

KCMH

Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Intl Airport KCVG

Dallas Love Field Airport

KDAL

James M. Cox Intl Airport

KDAY

Ronald Reagan Washington National Air-

port

KDCA

Denver Intl Airport

KDEN

Dallas

−

Fort Worth Intl Airport

KDFW

Detroit Metro Wayne County Airport

KDTW

Newark Liberty Intl Airport

KEWR

Fort Lauderdale

−

Hollywood Intl Airport

KFLL

William P. Hobby Airport

KHOU

Washington Dulles Intl Airport

KIAD

George Bush Intercontinental Airport

KIAH

Wichita Mid

−

Continent Airport

KICT

Indianapolis Intl Airport

KIND

John F. Kennedy Intl Airport

KJFK

Airport

Identifier

Harry Reid Intl Airport

KLAS

LaGuardia Airport

KLGA

Kansas City Intl Airport

KMCI

Orlando Intl Airport

KMCO

Midway Intl Airport

KMDW

Memphis Intl Airport

KMEM

Miami Intl Airport

KMIA

General Mitchell Intl Airport

KMKE

Minneapolis St. Paul Intl Airport

KMSP

Louis Armstrong New Orleans Intl Air-

port

KMSY

Will Rogers World Airport

KOKC

O’Hare Intl Airport

KORD

Palm Beach Intl Airport

KPBI

Philadelphia Intl Airport

KPHL

Phoenix Sky Harbor Intl Airport

KPHX

Pittsburgh Intl Airport

KPIT

Raleigh

−

Durham Intl Airport

KRDU

Louisville Intl Airport

KSDF

Salt Lake City Intl Airport

KSLC

Lambert

−

St. Louis Intl Airport

KSTL

Tampa Intl Airport

KTPA

Tulsa Intl Airport

KTUL

Luis Munoz Marin Intl Airport

TJSJ

7

−

1

−

25. PIREPs Relating to Volcanic Ash Activity

a.

Volcanic eruptions which send ash into the upper atmosphere occur somewhere around the world several

times each year. Flying into a volcanic ash cloud can be extremely dangerous. At least two B747s have lost all

power in all four engines after such an encounter. Regardless of the type aircraft, some damage is almost certain

to ensue after an encounter with a volcanic ash cloud. Additionally, studies have shown that volcanic eruptions

are the only significant source of large quantities of sulphur dioxide (SO

2

) gas at jet-cruising altitudes. Therefore,

the detection and subsequent reporting of SO

2

is of significant importance. Although SO

2

is colorless, its

presence in the atmosphere should be suspected when a sulphur-like or rotten egg odor is present throughout the

cabin.

b.

While some volcanoes in the U.S. are monitored, many in remote areas are not. These unmonitored

volcanoes may erupt without prior warning to the aviation community. A pilot observing a volcanic eruption who

has not had previous notification of it may be the only witness to the eruption. Pilots are strongly encouraged

to transmit a PIREP regarding volcanic eruptions and any observed volcanic ash clouds or detection of sulphur

dioxide (SO

2

) gas associated with volcanic activity.

Meteorology

7

−

1

−

61