AIM

4/20/23

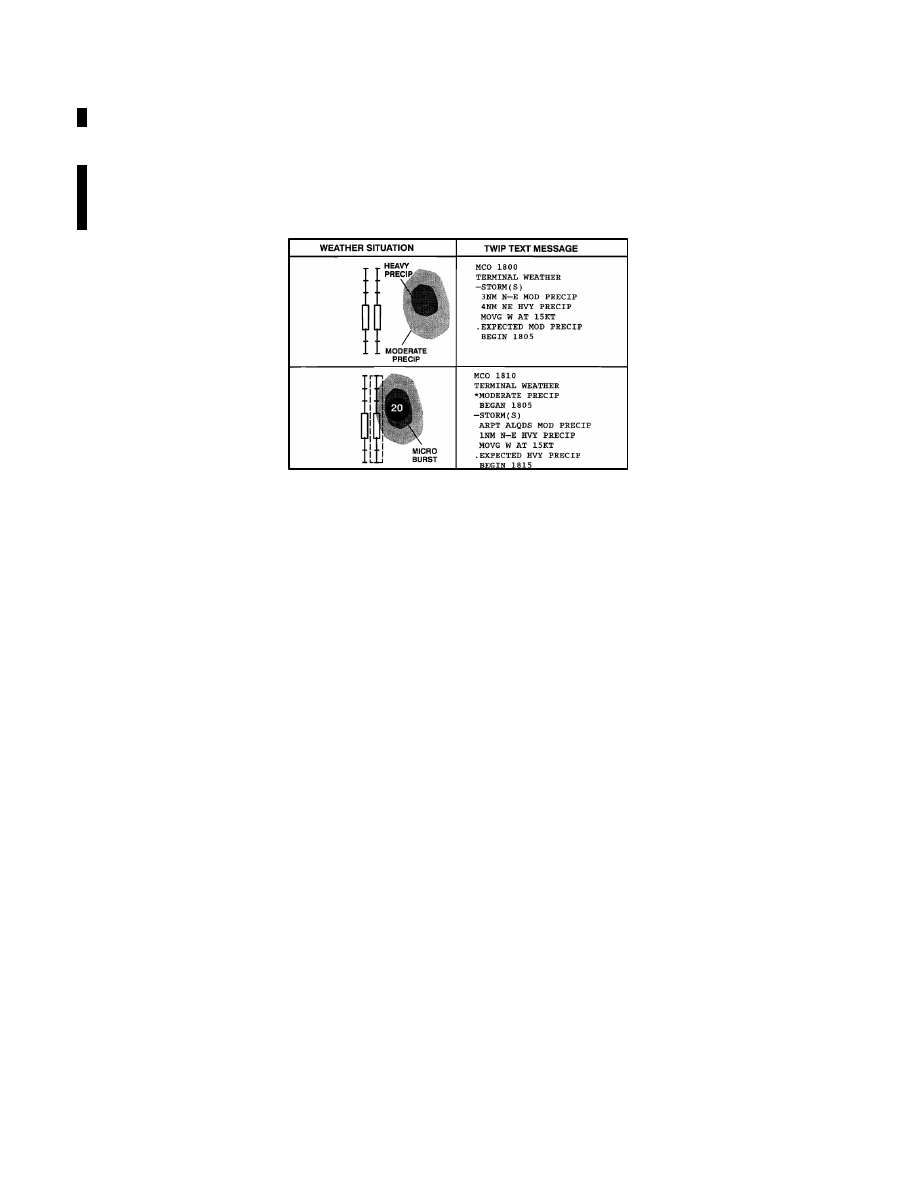

from ATC. The NAS has long been in need of a means of delivering terminal weather information to the cockpit

more efficiently in terms of both speed and accuracy to enhance pilot awareness of weather hazards and reduce

air traffic controller workload. With the TWIP capability, terminal weather information, both alphanumerically

and graphically, is now available directly to the cockpit for 46 airports in the U.S. NAS. (See FIG 7

21.)

FIG 7

−

1

−

21

TWIP Image of Convective Weather at MCO International

(b)

TWIP products are generated using weather data from the TDWR or the Integrated Terminal Weather

System (ITWS). These products can then be accessed by pilots using the Aircraft Communications Addressing

and Reporting System (ACARS) data link services. Airline dispatchers can also access this database and send

messages to specific aircraft whenever wind shear activity begins or ends at an airport.

(c)

TWIP products include descriptions and character graphics of microburst alerts, wind shear alerts,

significant precipitation, convective activity within 30 NM surrounding the terminal area, and expected weather

that will impact airport operations. During inclement weather, i.e., whenever a predetermined level of

precipitation or wind shear is detected within 15 miles of the terminal area, TWIP products are updated once each

minute for text messages and once every five minutes for character graphic messages. During good weather

(below the predetermined precipitation or wind shear parameters) each message is updated every 10 minutes.

These products are intended to improve the situational awareness of the pilot/flight crew, and to aid in flight

planning prior to arriving or departing the terminal area. It is important to understand that, in the context of TWIP,

the predetermined levels for inclement versus good weather has nothing to do with the criteria for

VFR/MVFR/IFR/LIFR; it only deals with precipitation, wind shears and microbursts.

7

−

1

−

60

Meteorology